Profiles In Nursing

Martha Ballard (1735-1812), Colonial Midwife and Diarist

Her remarkable diary reveals a legacy of nursing in 18th century America

She lived and died before Florence Nightingale was even born, but Martha Ballard’s diary still survives, providing us with a remarkable record of the lives of pioneer women and the practice of midwifery during the earliest years of the United States.

10,000 Entries

Even though she presided over hundreds of births, bore nine children herself and was an honored and respected member of her rural Maine community, Martha Ballard’s obituary read simply, “Died, in Augusta, Mrs. Martha, consort of Mr. Ephraim Ballard, aged 77 years.”

Had her descendants not saved and bound the jumbled sheets of her diary, her life would almost certainly have gone completely unremarked. In those ink-stained pages, Ballard had written an astonishing 10,000 entries detailing her life and work over a period of 27 years.

She wrote almost daily, usually about commonplace things like the weather, the progress of the garden, community events and the historic happenings of the time, but she also wrote about the many children she helped to deliver as midwife.

Social Childbirth

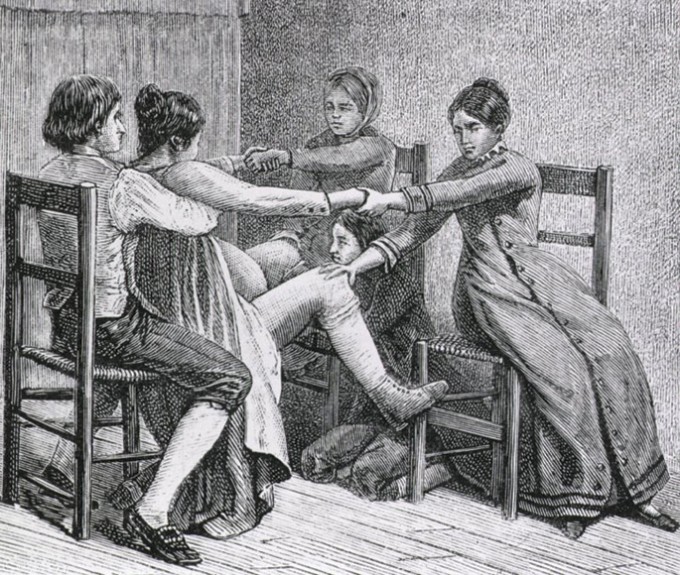

We don’t know for sure where Ballard learned midwifery, but it was most likely as an observer at the bedside. This was during what historian Laura Thatcher Ulrich, Ph.D., calls a time of “social childbirth,” when neighbors, female relatives and midwives might all attend a birth.

An observer would steadily increase her involvement until a day came when the experienced midwife was delayed or unavailable and the observer took over.

Ballard was unusual in that she could not only read (in that era, many girls were taught enough to read the Bible), but also write, using ink she made herself and quills taken from the geese she kept.

Despite her unusual capitalization and phonetic spelling, her diary entries are not too hard to decipher.

Colonial Life

The life those entries describe was not an easy one. Maine offers many challenges in terms of weather alone. Where Ballard lived — in rural Hollowell, along the Kennebec River — the water stays frozen from November until April. In one entry, Ballard describes her travels on a winter day:

Snow haul &rain. I left lady at 4pm as well as Could be Expected & walkt over the river. Wrode Mr. Ballard’s hors home. I had a wrestles night from fataug & weting my feet. I travild Some Rods in the snow where it was almost as high as mywaist. Stopt at mr Suels & warmd.

Ballard was proud of her work as a midwife, carefully noting and numbering each birth. She also kept the financial accounts of her practice in the margins. An “XX” marked next to the record of delivery indicated that her fee had been paid. In an era of barter, food, candles and utensils were all common means of exchange.

She also served the poor, including freed Black families, even if they were unable to pay, considering it part of her obligation as a neighbor.

Just like nurses and midwives today, Ballard sometimes had to balance her work with more personal crises. In another entry, she describes a moment of family tragedy:

At 4 & 20 in morn, mrs Edson was Deliverd of a Son which waid 7 1/2 lb and at 6 & 5 minnits of another Son which wd 8 3/4 lb. Left her at about 10, mr Ballard Coming there at that time. Enformd of ye Death of our Grand Son John Town, who Last thursday morn Drank So much spirit that Causd his Death which hapend yester Day at 8 in the morn. On my return from mr Edsons, mrs Weston Cald me in, Nathan Being Sick. I tarried with her this night. Left ye Child much Better.

Her relationships with local doctors were mixed. The physicians allowed her to attend autopsies (she was also the town mortician) and she was respected as an herbalist and pharmacist.

However, she was sometimes very critical of the doctors’ skills. She accused one male doctor new to practice of excessively using the narcotic laudanum and of being too aggressive with his instruments. After the death of one of the doctor’s infant patients, she called him a “poor unfortunate man.”

Immortality

Although Ballard attended more than 800 births in an era of very high infant and maternal mortality, she lost only five mothers and 20 babies. When she died at age 77, she could look back on a remarkable record of nursing and a life well-lived.

Amazingly, her diaries have survived for more than two centuries. In 1991, they became the basis of Laura Ulrich’s acclaimed biography, A Midwife’s Tale, which won a Pulitzer Prize and a host of other awards.

Ulrich later adapted her book as a PBS “American Experience” docudrama, which is still available on DVD. You can see clips from the film on the production company website, https://www.blueberryhillproductions.com/a-midwifes-tale

ELIZABETH HANINK, RN, BSN, PHN is a Working Nurse staff writer with extensive hospital and community-based nursing experience.

In this Article: Historical Nurses, Nurse Midwives, Pregnancy and Childbirth