Feature

Nightingale in Crimea

How a fiery newspaper article took Florence Nightingale into the Crimean War and sparked her crusade for hospital reform

On the morning that her life would change, Florence Nightingale sat down to her preferred breakfast of tea and kedgeree (a curry of rice, boiled egg, and smoked halibut) and opened The Times of London. It was October 12, 1854.

Thomas Chenery, the Times Crimean War correspondent, wrote:

It is with feelings of surprise and anger that the public will learn that no sufficient medical preparations have been made for the proper care of the wounded.

Just a few months earlier, Britain had joined France and Turkey in declaring war on Russia, partly to protect British passage to India.

Initially, the public had burst with enthusiastic patriotism. British troops were shipped off to battle in their summer parade uniforms, sure of a quick victory.

Now, Londoners were learning the truth about the war: It wasn’t going well for the unfortunate soldiers fighting in faraway Crimea, a land we now know as Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Superintendent Nightingale

Florence Nightingale was not yet a renowned public figure, but at 34 years old, she was a well-trained, experienced nurse. Born in Florence, Italy, she was better educated than most captains of industry and government officials of the time. She had flouted her parents’ wishes at age 25 when she traveled to Germany to study nursing.

For the past year, she’d been working as a superintendent of a London hospital. Since upper-class Englishwomen from respectable families did not hold salaried employment, her role was unpaid and viewed as charity work.

As a trained nurse, Nightingale was greatly dismayed by what she read in Chenery’s Times article.

A Hospital with No Nurses

Chenery reported that British soldiers had arrived on the Crimean Peninsula in uniforms better suited for a parade or fancy dress ball — a short-tailed red coatee with a high Prussian collar, two rows of gold buttons and fringed shoulder epaulets, over grey or cream-colored pantaloons.

After a few weeks on the battlefield, these frocks were in rags.

The British Army had given little thought for the feeding and shelter of the troops. As fall cold set in, there were no winter uniforms, boots, or heavy coats. Poor-quality tents offered little protection against mud and rain; the men lived on meager biscuit and salt rations.

Rather than being treated near the front, the wounded were ferried hundreds of miles away to a military hospital in the Turkish district of Scutari, near modern-day Istanbul. One-third did not survive the passage across the Black Sea.

At this point, it’s unsurprising to learn that medical care at the Scutari Barrack Hospital was appalling. Surgeons were in short supply, along with anesthesia, medicine, and linen for bandages. When a patient died, he was hastily sewn into his blanket and heaved into a mass grave so another wounded man could take his cot.

And the British public was scandalized to learn that the Scutari hospital had no nurses! In a jab intended to spur nationalist pride, Chenery wrote:

Here the French are greatly our superiors. Their medical arrangements are extremely good … they have also the help of the Sisters of Charity, who have accompanied the expedition in incredible numbers. These devoted women are excellent nurses.

Wartime Innovations

Today, we take such candid wartime reporting for granted, but in the mid-19th century, Chenery’s account was shocking. It was made possible by a recent technological innovation.

The necessities of war lead to inventions of all kinds. Think of the Internet, and GPS, developed by the U.S. government to track troop movements; even margarine was created to give Napoleonic soldiers a spoil-proof alternative to butter. The Crimean War contributed the widespread use of the telegraph.

After the French and English built telegraph lines linking their headquarters on the Crimean Peninsula with London and Paris, wartime news could travel in just a few hours, rather than the days or weeks it had previously taken by horse or steamship.

This also allowed a new kind of wartime journalism. Previously, newspapers received war bulletins in the form of military communiqués that were little more than cheery propaganda.

By contrast, Thomas Chenery traveled to the British Army’s front lines in Crimea and filed timely uncensored reports. As an employee of the Times, he could not be removed by the Army and shipped home (as the officer corps surely would have preferred). His coverage reshaped the British view of the war and generated public outrage.

Nine Days

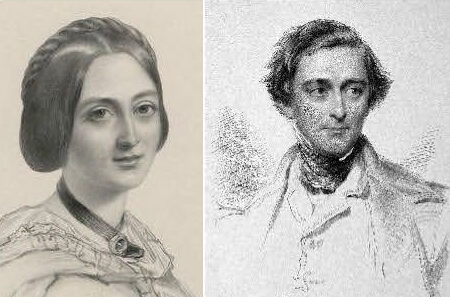

Florence Nightingale vowed to act. That morning, she penned a letter to her friend Elizabeth Herbert, wife of Sir Sidney Herbert, secretary of war, asking her to speak to her husband about Nightingale recruiting a team of nurses for Crimea.

By strange coincidence, Sidney Herbert had the same idea and also wrote to Nightingale that day. Their letters crossed in the mail.

With Herbert’s approval, Nightingale swiftly assembled a cohort of 38 nurses to travel to Crimea. She favored young women from the lower classes, assuming they would be better-equipped to withstand the hard work and difficult conditions ahead.

Nightingale recognized the need for what we today call culturally competent care. As about one-third of the British infantry was Irish Catholic, the group was later joined by 15 Catholic sisters.

Just nine days after publication of Chenery’s newspaper article, Nightingale and her nurses boarded the paddle steamer Vectis. The two-week journey took them down the western coast of Europe, through the Strait of Gibraltar, and past Sicily and Greece to finally reach Turkey. The nurses wrote of much misery and seasickness.

“The Kingdom of Hell”

During her initial rounds of the Scutari Barrack Hospital, Florence Nightingale must have felt like she’d descended into a scene from Dante’s Inferno. One can imagine the dank stench from the clogged drains and sewer pipes in the unventilated, overcrowded wards. The water supply was contaminated. Men injured by bullets and bayonets writhed and cried out in pain. Patients suffered from vermin infestation, scurvy, typhoid fever, cholera, dysentery, and diarrhea.

How appalling that in a war zone, disease was responsible for 90 percent of deaths!

Nightingale later wrote that the first seven months in Scutari were more deadly than the Great Plague of London of 1685. She described the hospital as the “Kingdom of Hell.”

“Commencement of Sanitary Improvements”

As could be expected, military officers were not thrilled with the arrival of a strong-willed Englishwoman claiming to be the new hospital superintendent.

Undeterred, Nightingale and her team of nurses buckled down to the task at hand. Before any effective nursing care could be given, the hospital needed a complete sanitation overhaul.

That winter, the nurses scrubbed walls with quicklime, organized wards into corridors of beds 6 feet apart, and constructed outdoor latrines. They washed soiled bedding and ragged uniforms — in most cases, the same ones the men had worn since leaving Britain.

Nightingale’s notes on some of the sanitation work done during this period include some distasteful details:

Handcarts or large basketsful of filth removed: 5,114

Sewers and latrines flushed (times): 466

Carcasses of animals buried: 35

Measuring Progress

Today’s business school maxim, “that which gets measured gets managed” was a concept Nightingale instinctively understood.

She set up a methodology for tracking the condition of the soldiers; their injuries, illnesses, and symptoms; remedies used; and the rates at which patients recovered or died.

In addition to her focus on improving sanitation, during her time as superintendent of the Scutari Barrack Hospital, Nightingale evaluated and recorded all aspects of patient care, from tourniquet technique to nutrition. For example, her statistical inquiry included the best way to feed 1,000 soldiers with just 26 cooking pots.

The Statistical Proof

A report Nightingale later published in London shows the impact of her work.

In October 1854, shortly before she arrived, the official mortality rate at Scutari had been 192 deaths per 1,000 sick patients. After sanitary improvements were completed, the mortality rate dropped to just 11.5 per 1,000 — a remarkable improvement!

To make sure members of Parliament understood the significance of the numbers, she included mortality figures from London military hospitals, where in 1851, there were 22 deaths per 1,000 sick patients.

In other words, military patient mortality rates in peacetime London were twice as high as in Nightingale’s wartime hospital in Scutari!

What Made Her so Effective?

Florence Nightingale’s assertive personality was definitely an asset in Scutari. She was able to stand up against a military establishment that resisted change, had little use for nurses, and resented her interference.

She also ruled her nurses with an iron hand. When they complained about “bossy Miss Nightingale” or were caught drinking or fraternizing with soldiers, they were dismissed and shipped home.

Her political connections were essential. Before she left, Sidney Herbert had authorized Nightingale to report directly to him, avoiding the military chain of command.

Money was not a problem either. She had personal funds and access to donations collected by The Times of London. So, when new boilers were needed to heat water for cleaning and laundry, she bought them herself — no arguing over a lengthy Army procurement process.

Her work ethic was legendary. She labored all day, then rounded on patients at night by the light of her kerosene lantern, earning the now-famous moniker “Lady with the Lamp.” Deep Christian faith propelled a commitment to the mission, even when she was stricken with fever. (She never fully recovered.)

Nightingale’s Legacy

The Crimean War ended in spring of 1856, yet Nightingale refused to leave until the last soldier was discharged from the hospital. She didn’t return to England until August.

We can read her meticulous report to see how many lives were saved at Scutari. Yet, even Florence Nightingale’s statistical skills couldn’t begin to measure the impact her efforts would have — not just on the soldiers of a now-forgotten war, but on nursing, hospital administration, and healthcare around the globe.

It was a triumphant nursing achievement.

CATHERINE RHODES is the editor and publisher of Working Nurse.

In this Article: Historical Nurses, Nurses at War