Profiles In Nursing

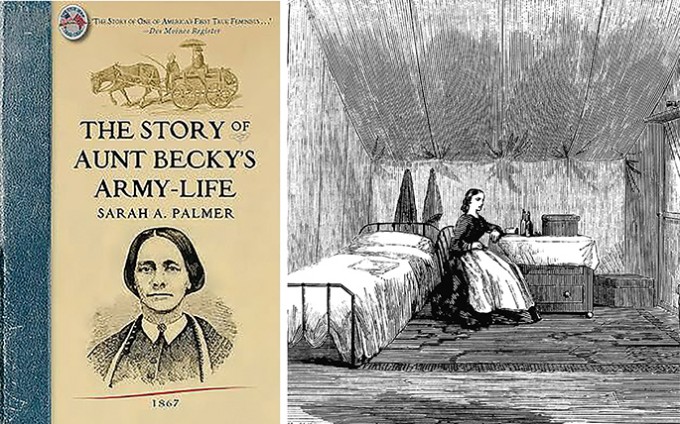

Sarah A. Palmer, aka “Aunt Becky” (1830–1908), Civil War Nurse and Memoirist

Her vivid wartime memoir is still in print

Sarah Graham Palmer Young, popularly known as “Aunt Becky,” was one of the best-known Union Army nurses of the Civil War, adored by many as a fierce champion of sick and wounded soldiers. Her vivid wartime memoir is still in print today.

Gone to War

Born in Ithaca, N.Y., Sarah A. Graham Palmer married at age 18 and became a widow by her early 30s. When her beloved brothers enlisted in the Union Army following the outbreak of the Civil War, Palmer promised them she would “go with them down to the scene of conflict, and be near when sickness or the chances of battle threw them helpless from the ranks.”

In September 1862, she kept that promise, leaving her two daughters with relatives and joining the 109th Regiment, New York Volunteers, as a matron, kitchen supervisor and nurse.

The Ideal Nurse

When the Civil War began, there were no nursing schools or nursing credentials. Battlefield medics and Army surgeons were all male. However, the shortage of caregivers had prompted the Army to consider female nurses, tasking newly appointed nursing superintendent Dorothea Dix with recruitment.

Dix considered the ideal candidate to be a woman between the ages of 35 and 50, in good health; of high moral standards; not too attractive; with good conduct, superior education and serious disposition. Her standards were so rigid that many women could not meet them, although some decided to volunteer anyway.

Palmer, only 32 when she joined the 109th, was somewhat younger and prettier than Dix’s ideal. When she first arrived at the crude Army hospital in Beltville, Md., she was greeted with such skepticism that it was five days before the other nurses arranged formal quarters for her.

Nevertheless, she soon won the respect and appreciation of her colleagues and patients for her dedication and compassion. Early on, she accepted the nickname “Aunt Becky” (suggested, at least according to some accounts, by a soldier in her care). Because so many of the soldiers were very young men — some as young as 16 — Palmer’s charges would sometimes call her “Mother.” Nevertheless, she would be popularly known as “Aunt Becky” for the remainder of her service and until her death 46 years later.