Feature

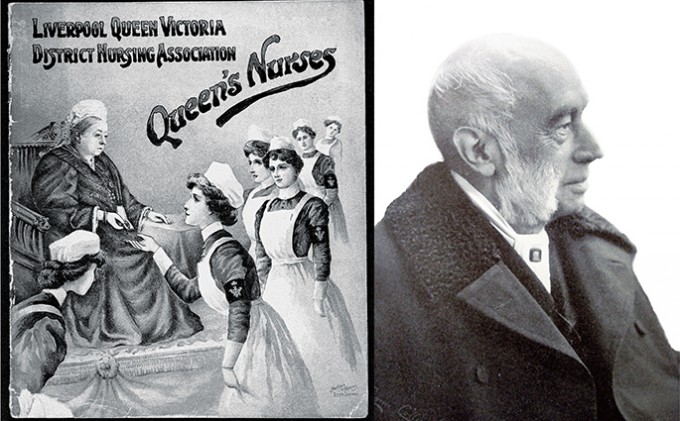

William Rathbone VI (1819-1902), Father of English District Nursing

How a Unitarian philanthropist urged Queen Victoria and Florence Nightingale to revolutionize Dickens-era public health

Although he himself was neither nurse nor physician, William Rathbone was one of the most important figures in British nursing in the Victorian era, revolutionizing healthcare for England’s poor and establishing a new model of nursing practice.

Faith, Grief and Philanthropy

William Rathbone VI was the eldest son of a successful Liverpool mercantile family also known for its many charitable works. Rathbone’s ancestors had been Quakers and his parents continued that tradition of public service, supporting a range of causes from slave emancipation to public education. The family’s motto was, “What ought to be done, can be done.”

As a young man, Rathbone became a Unitarian, inspired by his eloquent brother-in-law, the Rev. John H. Thom. Rathbone believed that affluence only increased one’s obligation to serve others, describing material wealth as “a trust for which [a man] owes an account to himself, to his fellow-men and to God.”

Rathbone’s involvement with nursing began in personal tragedy. In 1858, his first wife, Lucretia, became seriously ill while pregnant with their fifth child. Rathbone hired a private-duty nurse, Mary Robinson, to care for her, but Lucretia died on May 29, 1859, leaving him devastated.Rathbone’s involvement with nursing began in personal tragedy.

In 1858, his first wife, Lucretia, became seriously ill while pregnant with their fifth child. Rathbone hired a private-duty nurse, Mary Robinson, to care for her, but Lucretia died on May 29, 1859, leaving him devastated.

As he came to terms with his grief, Rathbone reflected on the comfort Robinson had provided his wife during Lucretia’s illness and considered the good such skilled care might do for others in need. Several months later, he decided to hire Robinson for a new assignment: in his own words, “to go into one of the poorest districts of Liverpool and try, in nursing the poor, to relieve suffering and to teach them the rules of health and comfort.” Naturally, he paid all her expenses.

A Letter to Florence Nightingale

At first, Robinson found this work almost too overwhelming to bear, but by the end of her initial three-month engagement, Rathbone said, “she came back saying that the amount of misery she could relieve was so satisfactory that nothing would induce her to go back to private nursing, if I were willing to continue the work.”

Rathbone was willing and eager to expand this project to other areas of Liverpool, but he soon discovered that finding additional nurses of Robinson’s caliber was no easy task. There was still no standardized nurse training, licensure or registration in Great Britain, so the quality of individual nurses varied widely.